For years, I have escaped to the beaches of Miami, Florida as an outsider looking to steal some fun in the sun. But thanks to an immersive site visit with the 2017 cohort of PLACES fellows, I possess a greater appreciation and understanding of Miami as a place filled with a rich mix of history and culture unparalleled by any other city in the country. Our time in Miami made the most of my senses, whether it was during our emotional grounding exercise on the sunny shore of Historic Virginia Key where we got to know one another personally, or during our savory Caribbean lunch at Clive’s Cafe in Little Haiti.

Yet, despite the exposure to all things that make cities like Miami beautiful, it is difficult to gaze past the savage inequities that are still fracturing the city’s communities of color. All the things that make Miami a beautiful place could not mask the trend that we are all familiar with in our own cities, and it hit me like a sack of bricks as we passed through Miami’s Overtown neighborhood.

Historic Overtown, a once bustling center for black life and culture regarded as the “Harlem of the South”, sits just northwest of downtown Miami in the shadow of failed urban renewal policies. The construction of Interstate 95 during the 1960s, which runs directly through Overtown, ripped through the neighborhood and displaced thousands of residents. The project set off a trend of population decline that has spanned decades. As we passed through the community on a packed van on our commute to Little Haiti, tears fueled by anger and hurt began to fall as I realized that this neighborhood’s story is far too common: a historically black place crippled by policies that are designed to wipe away its entire existence. This has been the story in other major cities—Nashville, New Orleans and my home of Atlanta, just to name a few.

Historic Overtown, a once bustling center for black life and culture regarded as the “Harlem of the South”, sits just northwest of downtown Miami in the shadow of failed urban renewal policies. The construction of Interstate 95 during the 1960s, which runs directly through Overtown, ripped through the neighborhood and displaced thousands of residents. The project set off a trend of population decline that has spanned decades. As we passed through the community on a packed van on our commute to Little Haiti, tears fueled by anger and hurt began to fall as I realized that this neighborhood’s story is far too common: a historically black place crippled by policies that are designed to wipe away its entire existence. This has been the story in other major cities—Nashville, New Orleans and my home of Atlanta, just to name a few.

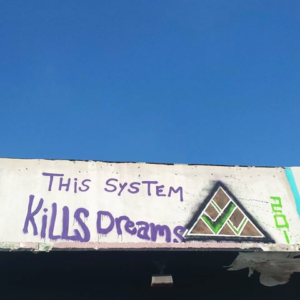

The anger grew as I realized that these development projects, reflecting billions of public and private investment, stand as monuments to structural racism and are painful reminders that people of color are repeatedly treated as disposable. This is still the case in 2017 as market pressures are encouraging developers and policymakers to rapidly gentrify cities while simultaneously displacing low-income residents and entire neighborhood-based institutions.

Later in the afternoon, we had a very timely discussion on strategies to disrupt the systems that act together to oppress communities like Overtown. And although philanthropy is actively addressing troubling patterns in the social sector, our call to action as fellows was to look for ways to dig deeper to address the root causes. Our facilitator, Bina M. Patel emphasized that the “problem with focusing on patterns is that you only change the scale or frequency of the pattern, rather than eliminating the pipeline – and this is not systems change”.

I had to take a moment here and ask: How seriously committed are we as funders in taking ownership of philanthropy’s role as a system that has historically perpetuated the very inequities it seeks to eliminate? In the case of development in places like Overtown, how long has philanthropy slept on the root causes that fuel displacement in communities of color, and what will it take for us to WAKE UP? We frequently heard that the “train has left the station” from some of the residents in Miami, suggesting that the development is happening too rapidly in the area and the system is too complex to disrupt. I may be oversimplifying the problem, but I don’t believe the rapid pace of gentrification is a cause for surrender. I believe philanthropy can play a significant role in the shifting power (dollars) that residents need to reclaim, protect, and determine the future of their neighborhoods.

I am now looking across the field to get a better picture of what share of philanthropic giving goes to supporting resident voices when compared to the amount of investment for physical development projects that fracture communities of color. These are the type of complex issues I look forward to untangling with other members of the ‘17 PLACES class. With equity as the priority for all of us, we recognize that philanthropy can’t really do systems change work if we don’t put people, especially people impacted by the broken systems we helped to create, at the center of all of our funding decisions.

Alex Camardelle

Alex Camardelle

Program Assistant

Annie E. Casey Foundation

Alex is program assistant for the Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Atlanta Civic Site, where he supports a place-based effort to strengthen economic security for children and families. Specifically, he works with senior staff and grantees to promote policy and practice improvements that aim to achieve equity for low-income communities of color in Southside Atlanta. Alex also leads the design of a strategy for stronger place-based investments in youth and young adult engagement and grassroots organizing. Before joining Casey, he provided legislative research support for various government and nonprofit organizations including Atlanta Public Schools, the Southern Regional Educational Board, and Louisiana State University. Through research advocacy, grantmaking, and thought leadership, Alex has helped community-based organizations and public systems develop new ways for activating and advancing a social justice agenda for the populations they serve.

Alex is currently working on a Ph.D. in Policy Studies at Georgia State University where he studies the social, political, and economic dimensions of policies that impact neighborhoods of color in the South. He holds a Master of Public Administration degree from Georgia State University and a Bachelor of Arts degree from The University of Alabama.