BY Cheri Souza, Hawai‘i Postsecondary Success Program Officer, Stupski Foundation, and 2025 PLACES Fellow

As I left Saint Paul, the message got louder; slow down and listen, the land is speaking.

Growing up in Hawaiʻi, understanding the precious relationship between ʻāina (land) and people was natural. I grew up between the beach and the mountains, and I learned early on that living on an island means caring for our finite resources. The Hawaiian proverb, He aliʻi ka ʻāina, he kauwā ke kanaka (The land is chief, man is her servant), captures this truth.

During our PLACES site visit, the call to listen was sharpened during four exchanges: Waḳan Ṭípi Nature Sanctuary, reclaimed and restored as a sacred Dakota place; the Hmong American Farmers Association (HAFA), building community wealth through land tenure and a food hub; a pilgrimage to George Floyd Square, where grief and resolve are held in public; and a chat with the Rondo Community Land Trust and the West Side Community Organization, where the community is working together to advance reparative actions.

Each visit underscored that land anchors relationships among people and ancestors, supports community wellness, and that philanthropy can either deepen erasure or fund repair.

As we kicked off our time together, we were challenged to examine how our identities granted us proximity to power or exposure to harm as we wrestled with how environmental stewardship without cultural respect could reproduce erasure. We used positionality maps and place-based reflection to see how our race, class, indigeneity/immigrant histories and institutional roles shape who has safety, voice and decision-making power on the land.

We also named how “green” projects that skip language, ceremony or community governance can reenact dispossession, while sharing repair practices like funding Indigenous-led stewardship, sharing board seats, aligning metrics to cultural and ecological indicators and, most importantly, allowing community voice and guidance to lead projects, evaluations and reporting.

Our first stop was the Waḳan Ṭípi Nature Sanctuary, where Maggie Lorenz and Gabbie Menomin shared how they were able to raise more than $10 million over eight years to transform sacred Dakota land known as Imnizaska, that had become a polluted dump site, into a vibrant 27-acre sanctuary that anchors cultural and ecological programming in the urban core, including a soon to be open cultural center. As we toured the site, a heavy rain began to fall and I received it as an ancestral blessing and cleansing and an embodied nudge to consider the physical positionality of the sanctuary nestled next to a railroad and feet from a freeway bridge under construction.

As I listened to Maggie, I heard how reclamation and restoration is wellness. This visit underscored the need to resource indigenous-led organizations, given that they receive only 0.6% of global philanthropic funding. It also urged funders to build budgets inclusive of language revitalization, signage, interpretation and ceremony as core programs (not extras) and ultimately to trust indigenous communities to lead their own projects.

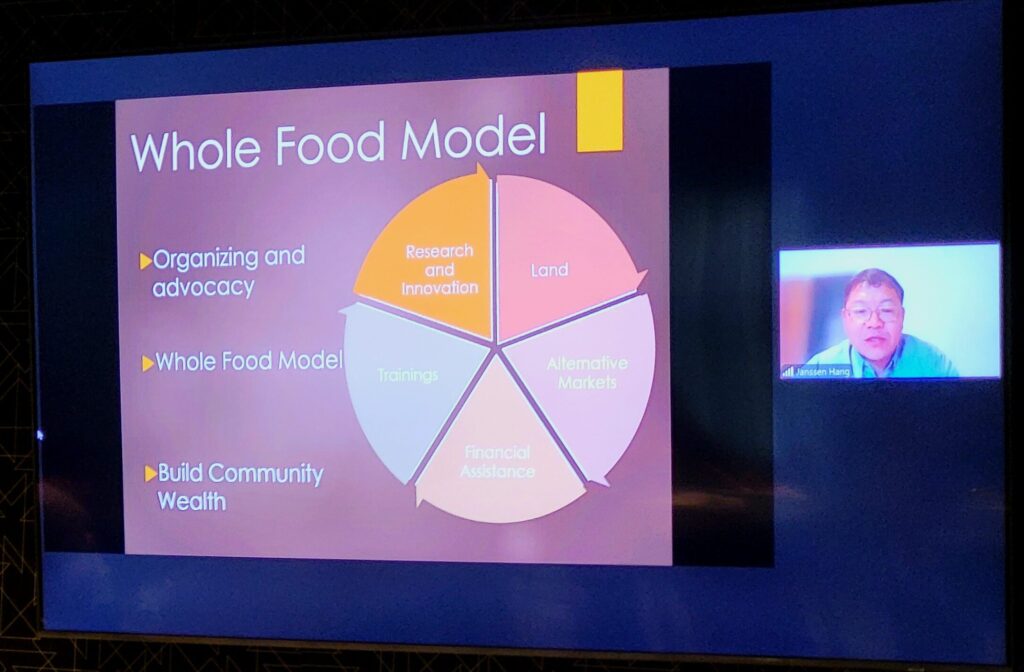

Rain kept us from visiting the HAFA farm in person, so Janssen Yang generously pivoted to a virtual briefing and walked us through HAFA’s model, where land tenure, training and market access have shifted immigrant families from income-earning to asset building. HAFA owns and manages a 155-acre farm and offers members long-term leases, intergenerational business education and a food hub that aggregates and sells members’ produce to Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) shares, schools, retailers and institutions. This integrated approach to social, economic and environmental justice has created real opportunity for many families.

Janssen shared a story of a farmer who once could not imagine passing the farm to his children because of constant uncertainty surrounding land access. However, after securing a long-term lease that stability reshaped his outlook and he now dreams of handing the farm down.

Listening to Janssen was a reminder that stability can heal by rewiring the nervous system, providing security so that people and families can plan for the future. This visit reinforced the need to finance community-owned agricultural infrastructure, multi-year leases, bilingual and intergenerational training and market infrastructure.

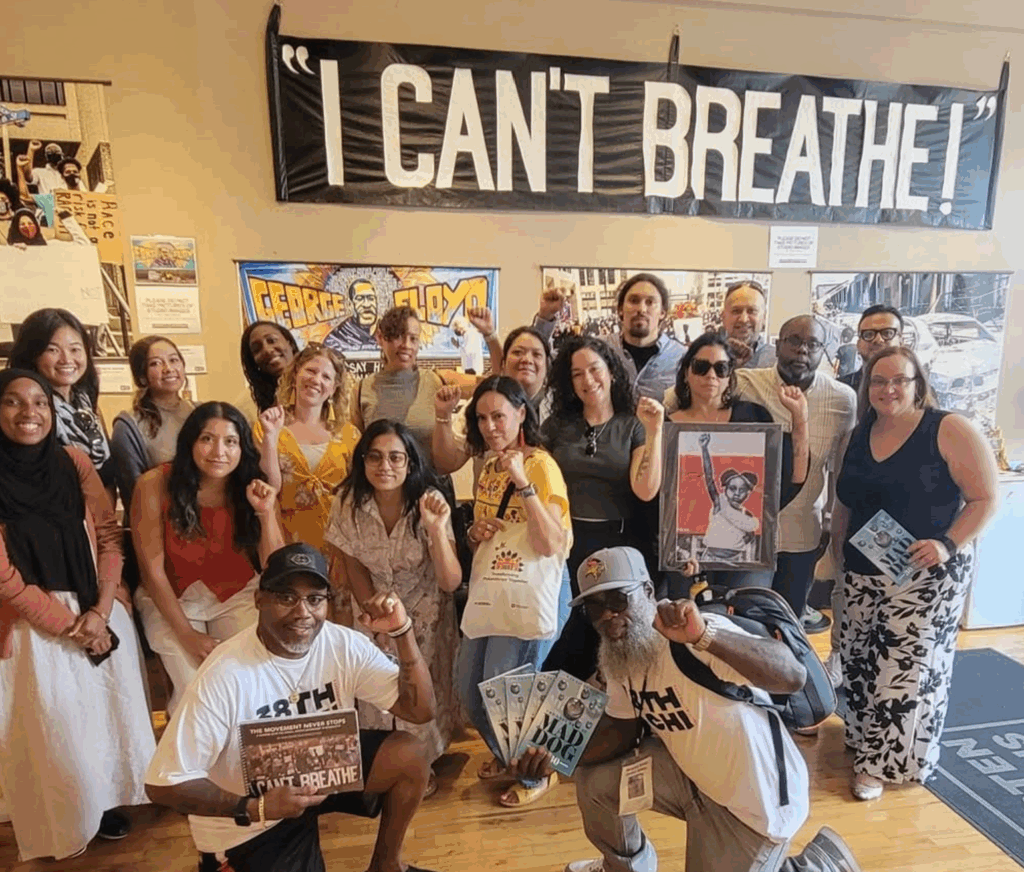

The next day, our group made a pilgrimage to George Floyd Square through Rise & Remember. We were guided by Georgio Wright, a community member who shared life in the Powderhorn neighborhood before and after George Floyd’s murder in 2020. I was unprepared for the grief, sadness and anger that rose as I walked through the Say Their Names Cemetery, reading markers and saying the names of children as young as seven.

At one point, Georgio asked us whether the “system” was broken. When most of us said yes, he replied, “No, it’s not broken. It is doing what it was designed to do.” The lesson for philanthropy is clear; name harm in place and let the people who live there lead the repair. Fund the caretaking of memorial spaces, healing-justice workers and organizing that turns story into policy. Prioritize long-term, community-governed work over shiny, temporary projects. When the spotlight moves on, dollars often leave too, and that churn can wound communities as deeply as the original harm.

(Photo Credit: KingDemetrius Pendleton)

(Photo Credit: KingDemetrius Pendleton)

Our final stop was in the Rondo neighborhood to meet leaders and elders from the Rondo Community Land Trust and the West Side Community Organization, groups formed in response to the economic violence of infrastructure projects and urban renewal.

Here’s why land ownership matters so much in Rondo: In 1956, a highway sliced through this historically Black neighborhood, taking about 700 homes and 300 businesses with it. Across the river on the West Side, a multiracial community with strong Latinx roots lost more than 2,100 families after flooding. With that history, community voice isn’t optional, it’s how these neighborhoods thrive.

Although operating in different communities, their throughline is simple; make everyday life better for the people who call these communities home. For funders, the move is just as simple; back resident-led planning and community ownership, and stick around long enough for power to grow and roots to hold.

In the end, everything circles back to land. Memory anchors health, and when sacred sites, farms and memorials are resourced, they serve as clinics for spirit and social fabric by creating a sense of belonging and engagement.

Governance heals too; who decides matters just as much as what gets done, and community rituals are a source of real medicine. Cultural practices are not separate line items, but should be woven together into a greater system.

Finally, repair runs on its own time, not quarterly reports, which means philanthropy must dig into multi-year commitments that move at the pace of planting, tending and harvesting.

Change canʻt wait, but it also won’t happen overnight. If philanthropy can honor land in the ways our indigenous ancestors did and align with community leadership and rhythms, we can move beyond funding projects and start supporting people and places as they heal together.

Mahalo, miigwech, thank you to the leaders and guides who steward these places and who welcomed us to learn on their homelands.

About the Author

Cheri Souza is the Hawai‘i Postsecondary Success Program Officer at the Stupski Foundation. She leads the Hawai‘i postsecondary success portfolio focused on holistic student support initiatives and work-based learning throughout the islands, with an emphasis on underrepresented students and rural communities. She is also a member of TFN’s 2025 PLACES Cohort.

Cheri Souza is the Hawai‘i Postsecondary Success Program Officer at the Stupski Foundation. She leads the Hawai‘i postsecondary success portfolio focused on holistic student support initiatives and work-based learning throughout the islands, with an emphasis on underrepresented students and rural communities. She is also a member of TFN’s 2025 PLACES Cohort.

Photographs provided by Cheri Souza.